My dad loves this story:

When my dad and mom were still dating, my mom made him artichokes for dinner. As a midwestern boy raised on canned green beans and ambrosia salad, artichokes were as foreign as escargot. She asked him to go to the kitchen and taste the artichokes to see if they were ready. He picked out a soft green leaf from the pot and tasted its bitter exterior. Barely able to swallow the first bite, he tells my mom the artichokes were not ready. Nevertheless, my mom checks the artichokes just to be sure and yells back at him, “What are you talking about?! These are perfect!” And my dad braced for a long dinner.

They sat at the table, and my dad picked at his artichoke as if it were an alien egg. But then, my mom peeled back the layers of sharp green leaves to reveal the buttery and flavorful heart. A smile spread across my dad’s face. He loves artichokes now.

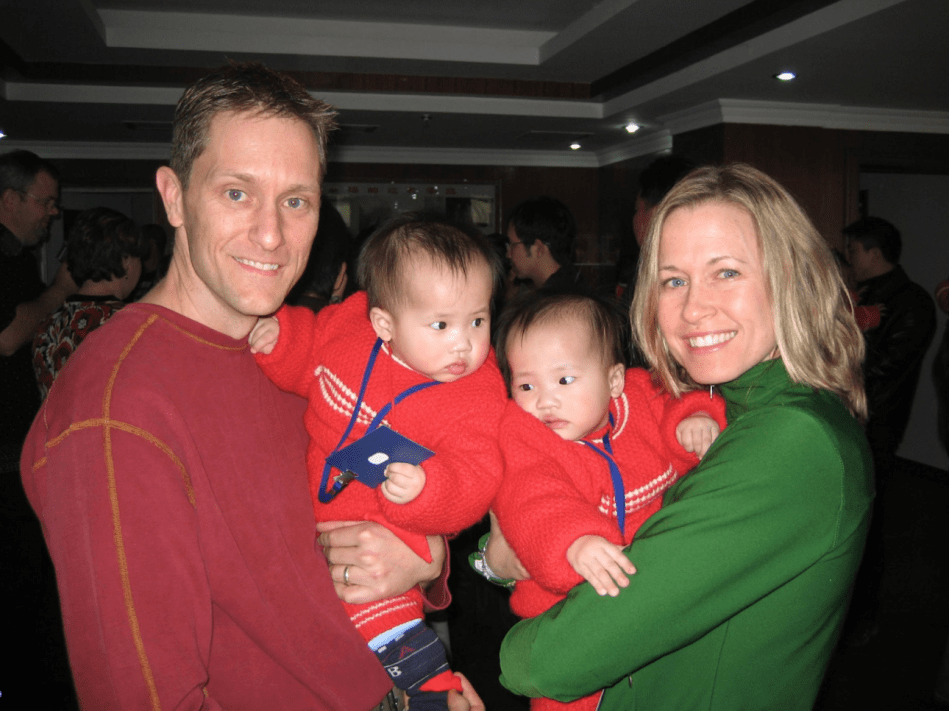

My parents fell in love over artichokes; little did they know, 12 years later, they would adopt two little artichokes for themselves.

﹏

I am an artichoke without a heart. An enticing green pinecone with a secret on the inside. But when someone finds my core, it’s a truth much harder to swallow.

On your first encounter with me, I’ll tell you my Chinese name (which I can’t even pronounce correctly). On your second encounter with me, you’ll hear that my class load includes lowly Chinese Beginner II, and I might catch your eyebrows twisting in confusion. On your third encounter with me, you may see the family selfie I have as my phone background, and if you’re smart enough, you might figure out the story yourself. But you probably won’t even need to at that point because I’ve already told you the truth on my second encounter with you, since I can’t stand that stupid, confused look on your face.

I think the most pungent part of being heartless artichoke is that while I am not Asian, I am certainly not white either. I am a nonbinary race, but not in the same way the child of a transracial couple is. They are multiple races, but I, in a way, am neither. I am lost in a cavernous echo of my own hollowed history.

Since arriving in New York City, I feel like I am discovering my race all over again.

I remember in 3rd grade when I ate my mac and cheese with chopsticks out of my thermos during a break during my gymnastics practice. One of my teammates asked me if I was born knowing how to use chopsticks. I began to laugh before realizing that she wasn’t joking.

“Um… no… I had to learn, I guess,” I squeaked out, now self-conscious with every bite.

I remember in 9th grade when my friends suggested we think of cartoon lookalikes for each other. We were doubled over laughing at one girl’s uncanny resemblance to Megamind when she pulled her bangs back. Then, we were standing in rigid silence when we got to my Chinese face.

“I’ll be Mulan,” I said to cut the silence.

The family selfie I have as my phone background.

Conversely, in Asian spaces, I am bombarded with names of cultural dishes I don’t know and conversations where the only words I understand are “I,” “then,” and “because.” But, in the same way I play along and laugh off microaggressions from my white friends, I simply turn the outer corners of my mouth up and nod my head in an effort to hide my otherness. I read once that if you just copy what the other people around you do, people will like you more. And so I obsessively watch the way these Asians move their heads and furrow their eyebrows to emulate it myself– if I convince them, maybe I can convince myself too.

My reckoning on race and my place in Chinese and Asian spaces led me to think about the transgender movement and its tension with transracialism. Transracialism describes people who identify as a different race than the one they were born into. The most headlined example is Oli London, a social media influencer who, despite being born British and white, identifies as Korean and spent an estimated $250,000 on 20 cosmetic procedures over eight years (Smith 22). People who support London’s actions argue that if someone is allowed to change their gender, they should be able to change their race. Opponents argue that races, specifically minority groups, have trauma that stretches thousands of years that one cannot simply insert themselves into, whereas the struggles of individual genders don’t share the same intergenerational history. I am a blaring green asterisk, as the conversations fail to acknowledge people like me: transracial adoptees who have the face of minorities but none of their generational trauma.

What many forget (or don’t know to begin with) is that race or categorization of humans based on shared physical qualities didn’t exist until the 16th century. The idea of race is, debatably, as meaningless as the idea of gender. And yet, transracialism continues to receive public backlash while transgenderism receives support and political attention to protect transgender communities.

I don’t write this in an effort to bash transgender movements or express my support for transracialism. Rather, I wonder, why are they treated differently? Why do I feel I cannot explore my racial identity to the same degree I could explore my sexual one?

In a physical sense, I cannot try on whiteness like a skirt or bleach my hair in the same way a trans man cuts his. But the conflict is deeper than that. Not only is racial exploration not physically possible, but it also feels emotionally wrong to claim the title of white. I feel myself abandoning a history, a culture, that I will never be a part of, but nonetheless am connected to. I wonder why a trans man does not feel the same conflict. Does he not feel bad for leaving behind his femininity? Abandoning his community?

To answer these questions, I attempted to find trans voices. Unfortunately, to no avail. I believe I fail to find trans people who feel bad “abandoning their community” because they’re leaving a community that never felt like theirs. But for me, I feel I cannot abandon my community because, in a way, it is all I have. At the beginning of this essay, I lamented over my Chinese name. One ought to wonder why I don’t just go by a European name like many others, but I find myself refusing to give up my name, even in the struggles it causes me, because it feels like a tether to a history someone told me long ago not to let go of.

When I chose to come to New York City for college, I was motivated by the idea of diversity, specifically, the high Asian population at NYU. Coming from a smaller public school in Missouri, I hoped to find more connection with my Asian heritage by surrounding myself with others who looked like me. In many ways, this wish has been granted. I am rarely the only person of color in a room and have gotten involved with several cultural clubs on campus. Despite this, the diversity at NYU is not the silver bullet I imagined it to be.

It’s as if I am in the crate with all the other artichokes, and I can hear their heartbeats. While not in perfect unison, they are musical and warm—proof of life. I dance to the beat, but when I put a hand to my own chest, there is nothing but silence. This silence turns into loneliness when all the other artichokes go to bed. They lie close to each other’s warm hearty bodies and feel their rhythms come to a slowed regulation. But my heartless body never rests. It sits in tense anticipation of them finding out my hollow secret.

When I think back to the story my dad loves, I wonder if it would have been different if the artichoke he ate didn’t have a heart. Would he be so madly in love that he could choke down the heartless bud? Forced a smile across his lips and told my mom he appreciated her hard work? I like to think he would have. Because if you love a person enough, you would eat 100 heartless artichokes. You might even adopt two little ones for yourself.

By An-Mei Deck

0 comments on “Sincerely, Artichoke”