Tipping waiters at restaurants and saying “bless you” after someone sneezes were both odd and entirely foreign concepts to my parents when they first came to the United States. As immigrants from China, they had a limited understanding of American life.

These weren’t the only norms that differed from what they grew up with. In China, they didn’t grow up expressing gratitude or affection through words, but in the United States, saying “I love you” and “thank you” are common ways people show appreciation for those close to them.

Growing up, a simple “再见 (zài jiàn)” bye was my cue to close the car door and walk into school. I’d watch as my classmates and their parents easily exchanged their habitual “I love you’s” as I hopped out of the car, craving the same verbal affection, wondering why my parents didn’t love me the same way.

It was discouraging that my peers’ 90% scores would be celebrated, while my 97% made my parents wonder where the other 3% went. When I’d show my parents my drawings, their response would be “还行吧 (hái xíng ba)” not bad at best. I couldn’t understand why my parents never told me that I’m smart or talented. I was always left wondering: Why are “I love you” and “I’m proud of you” forbidden in my family?

In the summer before fifth grade, my family and I took a trip back to China. My aunts, uncles, and cousins took my sister and me wherever we wanted—whether that be amusement parks, shopping centers, or cities. They also made sure my sister and I always got the first bite of food, and the fridge was always stocked with our favorite snacks. I would say “谢谢 (xiè xiè)” thank you, only to be reminded, “对家人不用这么客气” no need to be so polite to your family. They made it seem like nothing. But why not? If we’re grateful, shouldn’t we let each other know? Expressing “我爱你 (wǒ ài nǐ)” I love you felt out of place, and it was like they didn’t expect anything from us since seeing us happy was enough. Only then did I realize the norms I grew up with had no place here.

It didn’t take long before I started reflecting about my parents. What about the early mornings Mom woke up to make sure I had my favorite foods packed in my lunchbox? What about the princess stories Mom read me every night to make sure I’d sleep well? What about the times Dad spent hours doing math with me, even when he had hours of his own work to do? What about everyone they left behind so I could have the happy, healthy, and privileged life I have? How hadn’t I realized that this is what it meant to be loved?

They never expected anything from me in return, not even a “谢谢 (xiè xiè)” thank you.

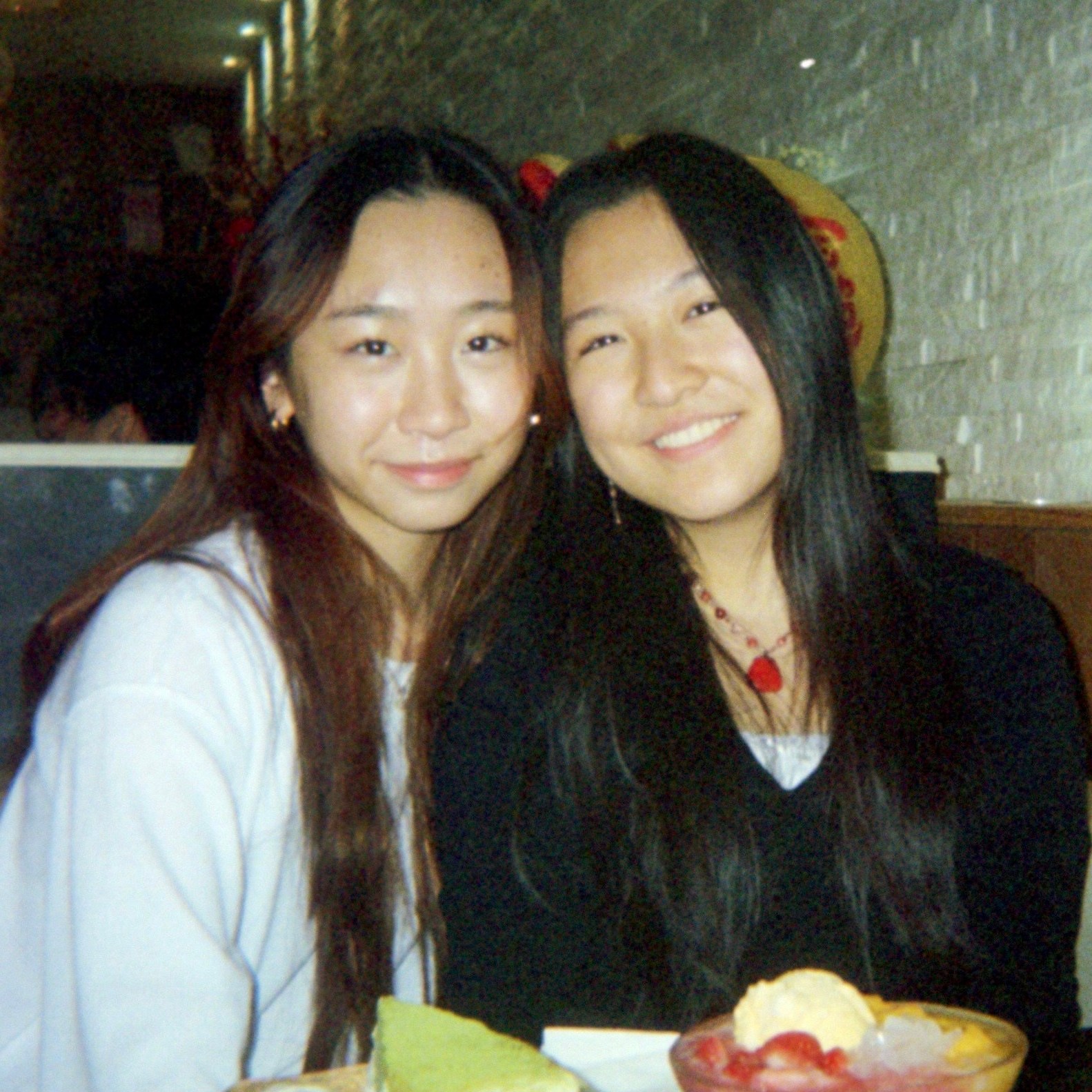

As I grew older, I began to realize that this dynamic is quite common in Asian culture, and many Asian people who grew up in the West have similar experiences. Reflecting on how love translates across cultures, I spoke with my friends, Yifan, Natalie, Lyrica, Azelin, Lisa and Jessica, who are also children of immigrant Asian parents to further explore this.

I first asked how often their parents say “I love you,” and how often they say it back. The results varied, but most expressed that it isn’t an everyday occurrence and happens more under special milestones, achievements or difficult times. Sometimes, it’s also easier to express it indirectly, like sending a text message, for instance.

As Yifan shared, “Sometimes they tell me to my face, but most times they just text me after we FaceTime. After I grew up, it wasn’t that natural to say it to my face because it’s kind of awkward.” However, this dynamic isn’t universal, as Lisa shared, “The words ‘I love you’ are still exchanged daily in both Mandarin and English. My mom likes to hug me a lot, and we still link arms whenever we’re walking together,” which contributes to her feeling comfortable showing physical and verbal affection with her friends.

In households where another language is primarily spoken, many expressed that if it’s said, it’s usually in English—emphasizing the cultural differences between Asian and Western societies. In Asian cultures, many feel there’s a stigma attached to expressing emotional vulnerability, which could manifest in avoidance of certain topics with parents, a separation of what’s said in English versus the mother tongue, or difficulty in navigating emotions. With her parents, Natalie communicates “strictly in English for deeper things, but never deep things like family relationships or introspective stuff,” showing differences in how and what can be shared with her parents.

Similarly, Azelin reflected, “I’m very grateful for my parents, but I feel like it’s really hard for me to be vulnerable in front of them, especially my dad. Honestly most of the topics we cover are strictly about school or politics, which can be a mess.” Lyrica’s parents are sometimes “colder and more stern when [she] gets emotional, because they believe that getting emotional doesn’t change anything or help in any way,” which is a common belief many Asian parents have.

Just like me, my friends have also had difficulties navigating these cultural differences. When asked if they’ve ever questioned their parents’ love for them, Azelin expressed, “When I was younger I always did. I don’t think I ever felt really loved in their presence, but when I think of it later, I notice how much effort they put into protecting me.” Like many of us, she struggled to grapple with the lack of verbal affirmation, especially in a society that heavily emphasizes that type of validation and assurance. Similarly, Jessica now acknowledges that her parents always put her first and do anything to make her happy. They’ve done the same throughout her life, but it was only more recently that she became aware of it. Their parents’ implicit actions of care led to doubt and misunderstanding, leaving them just as confused as I once was. It wasn’t until later that they began to realize and accept the differences in how their parents show affection.

Asian parents are also known to be more logical than emotional, which can lead to countless hours of what seems like criticism but what they see as showing concern. As Lyrica reflects, “In hindsight, some of their actions I found annoying, I now realize were done out of love, such as long lectures and criticism on seemingly simple things and ‘nagging.’ In the end, they listen to me and help me find solutions.” This goes hand in hand with how Asian parents show their love through acts of service. Whether that be apologizing with a bowl of cut fruit or saying “I love you” by cleaning their children’s bedrooms, Asian parents seem to have their own love language. Lisa’s dad “shows his love through acts of service, whether it’s cooking on Sunday mornings or taking [her] on drives when [she] [feels] low,” showing the translation of love into actions.

I’m grateful that my relationship with my parents has significantly improved over time as we’ve learned to navigate understanding the differences in our values. Through our countless misunderstandings, my parents have gradually come to recognize that my sister and I value some verbal affection, and they’ve started to express love for us through words more often. My sister and I also began to understand the differences in how they were raised and became more aware of silent gestures.

I’m especially appreciative of my relationship with my mom which we’ve strengthened over time — I can now openly share most of my emotions and experiences with her. Now that I’m in college and we’re not able to see each other as frequently, we’ve adopted a new way to express our care and support for one another. I’m thankful that she checks up on me through the phone often and comes to visit me between classes. I’ve also learned to communicate in my parents’ love language, whether that be bringing their favorite cold skin noodles from Xi’an Famous Foods every time I go home, or reaching out to call at the end of the day. Although we don’t frequently express verbal affection, there’s an unspoken mutual understanding.

When I revisited China last summer, I had a newfound receptiveness to silent affection, where exchanging “我爱你 (wǒ ài nǐ)” I love you began to feel unnecessary. I’ve come to learn that a lack of vocalization doesn’t mean an absence of love.

Maybe love cannot be quantified through words.

0 comments on “Love in Translation”