artwork by Ann Lee

By Jamie Huang

My childhood was spent in mismatched Disney princess tees and colorful, sparkly skirts, followed by an adolescence of cropped tanks and baggy jeans. Nothing about my style ever screamed or even whispered Asian culture. During my preteen years, I remember feeling restricted to certain traditional garments, with an absence of casual and “cool” culturally-inspired clothing to wear. Even then, the conventional clothing available never appealed to me, as heavy societal pressure greatly discouraged me from completely displaying myself with my culture. I was embarrassed about my culture more than ever.

Seeing the types of Asian-inspired clothing available on the market didn’t help. There was always something off about the clothing—whether it was the patterns or the inappropriate adaptations, none of the options felt like something I desired nor felt proud to wear. Zara and Topshop, for instance, have both released bodysuits featuring Chinese floral patterns, labeling the products as “Oriental”—a prime example of how brands sexualize various Asian styles and lump them into one broad region of “Eastern,” completely missing the actual influences. “Oriental” is a loaded word; outright using it for a culturally inspired look is quite offensive as it reduces an entire culture to one derogatory word. The decision to use this term shifts their claimed cultural appreciation to cultural appropriation, a purposeful disrespect aimed at profiting from it.

To add fuel to the fire, Western companies seemed to adore commercializing Asian culture, regardless of whether they remain true to the culture or not. In 2017, Vogue photographed White and blonde model Karlie Kloss for a Japanese-themed piece. Stylist Phyllis Posnick, who isn’t Asian, much less Japanese, embellished Kloss in traditional Japanese garments and plastered her face with aggressively pale makeup. Vogue had her pose with a sumo wrestler—a cultural touch to spice up their bland catalogs. Vogue is only one out of countless brands that exploit Asian culture to benefit their needs.

I was never fond of how Asian culture, specifically Chinese culture, was portrayed in the media and interpreted by society. It was a perpetual cycle of intense scrutiny, judgment, and disgust. The inevitable consequence of my embarrassment was that it pushed me to resist my roots. I credit part of my internalized racism to the incorrect stereotypical depictions of my culture in mainstream media.

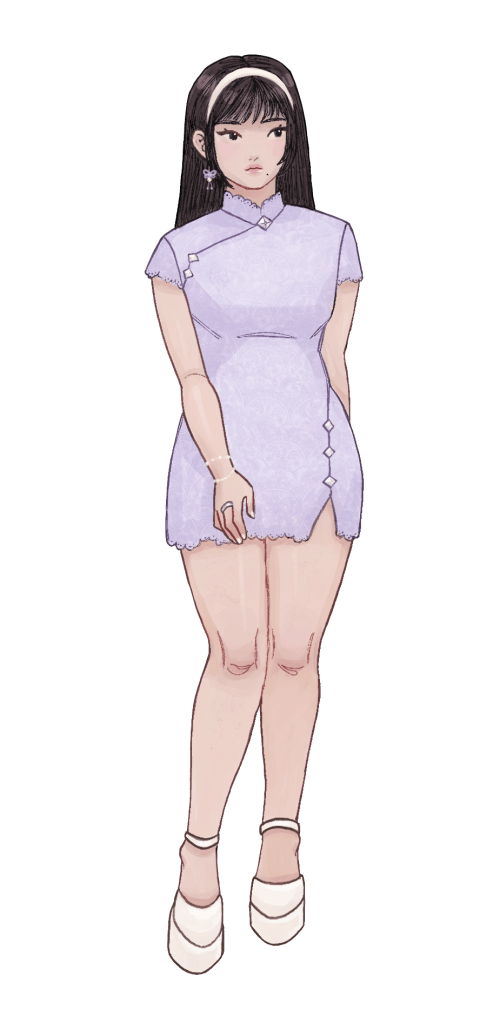

But as I walk into my last years of adolescence, I’ve realized there’s less and less to be ashamed of. Gliding into a year of self-love and care, I am proud to witness my generation unapologetically take their identities in stride. Clad in cropped qipao tops, silk floral shirts, and even traditional Hanfu, people of my race and generation proudly strut down sidewalks adorned in unique Chinese fashion—though not limited to such—claiming back our heritage through style, with style.

Countless people in China have declared their own statements of identity by participating in the Hanfu Movement. This movement aims to revive traditional Chinese Hanfu clothing as a nod to Han culture and a means to promote Chinese heritage. It’s the shrug of confidence we’ve needed.

The Modern Hanfu Movement began in 2003 as an initiative to launch the Han Chinese cultural renaissance. Hanfu (汉服) is the oldest traditional Chinese clothing. The style generally consists of a Paofu (袍服) or ru (襦) robe for the upper body and a qun (裙) skirt for the lower body. Despite the absence of dedicated retail outlets, numerous Hanfu enthusiasts boldly began wearing these garments in public. Only in 2006 did the first physical Hanfu store, Chonghui Han Tang (重回汉唐), open. In 2019, the estimated revenue sales for the Hanfu market came out to be nearly $200 million U.S. dollars, indicating the high demand for traditional clothing. Since then, much more has been done to promote Hanfu as a symbol of pride and national identity.

My generation has taken to social media platforms to brandish their creative styles. Many have incorporated Chinese influences—patterns, jewelry, and cuts—into their clothing. Others have also opted for traditional clothing. Videos of these styles have gone viral on platforms like TikTok, where compilations of various streetwear outfits are displayed, including Chinese styles. These videos receive millions of views—a promotion of Chinese culture itself. Though originating from Asia, these trends have started to reach America in the form of jewelry, media, paisley suits, and more. This endless ebb of inspiration from one country to another showcases the boundless creativity and resilience of people, bringing a strong sense of acceptance, pride, and belonging to Asians globally.

The garments worn in these videos can be attributed to rising Asian creators. Asian designers, despite all resistance, have endured the industry and made it out on top, bringing their cultural roots with them. Cheryl Leung is one of them.

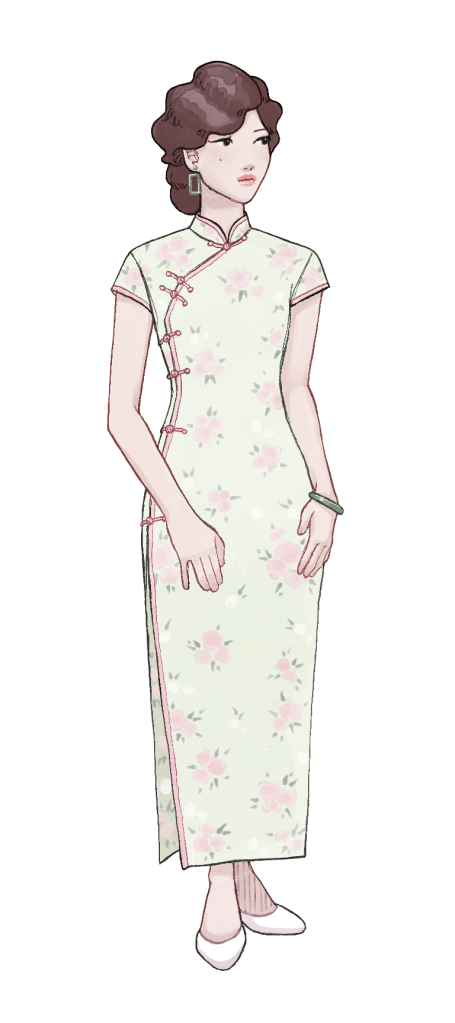

Leung founded Sau Lee in 2014, a fashion label known for its contemporary take on the traditional cheongsam. She beautifully combines the essence of Chinese heritage with modern-day Western fashion—creating a fusion of different styles that can be worn daily. Her pieces typically consist of her own take on traditional clothing like the qipao.

The qipao comes from Manchu’s changpao (長袍, also known as changshan, 長衫) and is a figure-forming dress with a collar and two side-slits. The dress usually has Chinese frog fasteners on the lapel and collar. It can be short or long, with sleeves or without. The qipao is the clothing of the Han women, but it has been famously picked up by Hong Kong, Shanghai, and Beijing.

Its long history has threaded the dress into the fabric of Chinese culture. Between the Han Dynasty and the Qing Dynasty, the men’s patent was the “changpao,” a one-piece, while women were restricted to two-piece clothing—they were forbidden to wear one-piece robes. The qipao dress symbolized an opportunity for women to reclaim control of themselves. It signified female empowerment as it offered women an option for one-piece clothing, which only men had access to during the Qing Dynasty.

Leung’s work, like many others, serves as a source of inspiration and a representation of Asian culture in the fashion industry. Pieces like Leung’s continue to attract praise from millions of viewers online, including me. Seeing an abundance of appreciation for my culture, in its authentic form and not the fabricated version portrayed in the media, has greatly normalized and eased me into embracing my roots. The authenticity of cultural representation in fashion allows others to recognize us for who we are—it’s gifted me the opportunity to grasp my roots and brandish them as I should have been doing all along.

Fashion is not just about clothing; it serves as a statement of pride and appreciation. Particularly now, fashion acts as a form of self-expression and artistic output—it is incredibly vital to shaping one’s identity. Choosing to incorporate Asian influences in styles today is important to many: it is a declaration of heritage and cultural connection, a firm grasp on one’s roots. This is why the fashion choices of Gen Z are so vital. By infusing our daily lives with elements of our heritage, we compel other cultures to acknowledge and recognize us. It’s a way for us to authentically represent ourselves, and what better medium than clothing to do so, subtly, yet unmistakably?

Jamie Huang is a freshman in Liberal Studies. She plans on majoring in MCC at Steinhardt with a minor in Creative Writing and BEMT. Jamie is an avid lover of literature—whether that entails fiction, nonfiction, poetry, lyricism, or rambling freewrites, she loves it all.

0 comments on “Reclaiming Roots: A Modern Twist on Cultural Fashion”