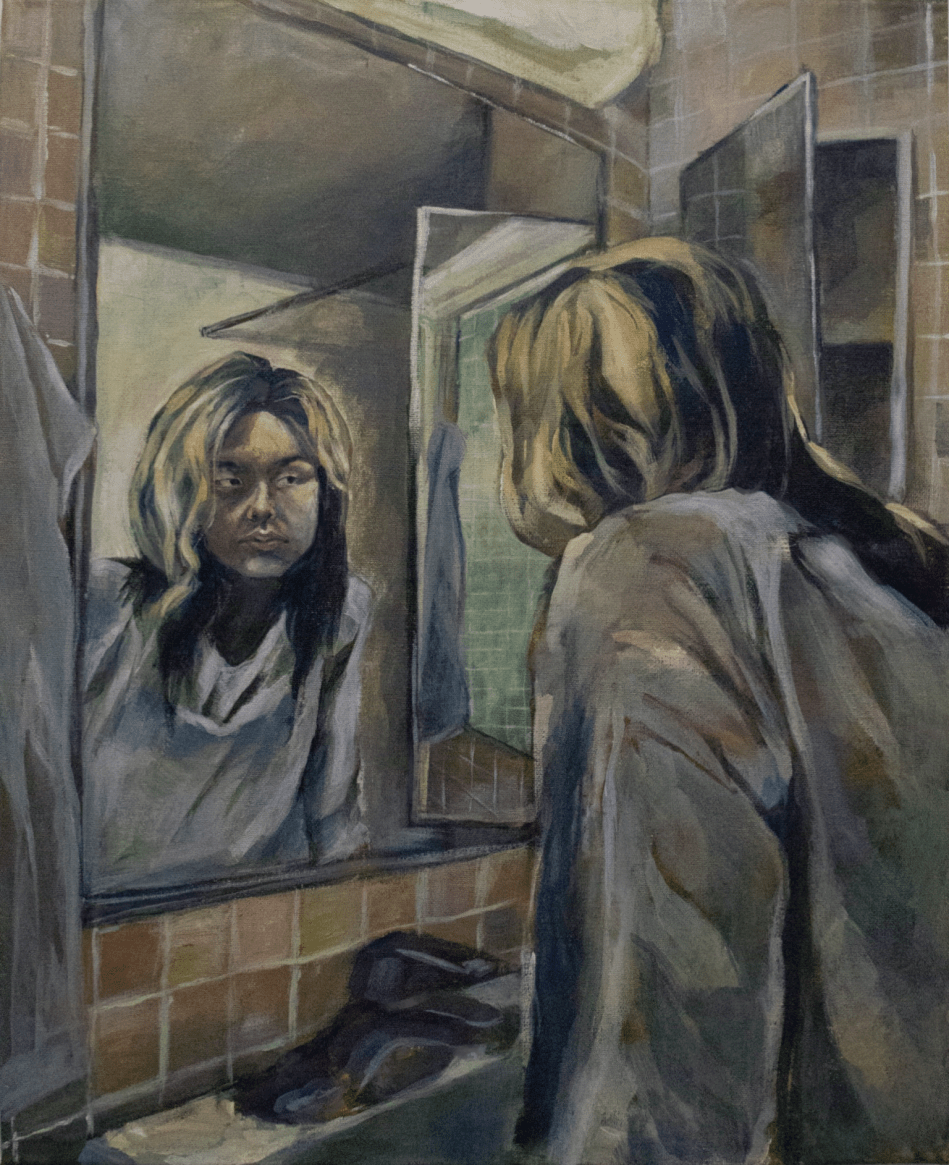

Artwork by Cynthia Li

By Cynthia Li

I find having a semi-traumatic experience at the Chinese hair salon, a pretty universal Chinese kid experience, when your mom takes you to a hairdresser who’s really listening to her words more than your own and you sit and pray they don’t chop off too much of the hair you’ve been diligently growing for the past few months. And while I thought that that had been a thing of my 12-year-old self’s past, the summer of my 17th birthday I found myself close to tears when I looked in the mirror and found my hair sitting at solid ear length. I remember trying to make it work, getting up early before school to style it, pinning and gelling it back. But as I grew lazy and my hair grew a minuscule amount longer, I just felt ugly with what I’d call today a “fuck ass bob.” It was my last year of high school, the first year I was back in school after the pandemic, and I had to take my yearbook photo with this nasty haircut. I went to school feeling the most insecure I’d felt in a long time, like the boys I liked wouldn’t look at me, and I’d sink into the background of just another Asian girl with a horrible haircut. Maybe it was how many hours I spent online, but I was starting to see all these Cali Asian girls, so pretty and hot and confident with hair dyed a gorgeous creamy blonde, and clicked immediately in my head, what I had to do. I knew I had to be blonde at that very moment. So I threatened my mom that if she didn’t take me to bleach my hair, I would order bleach on Amazon and figure it out myself.

The way I have my hair bleached now is the same as it’s been since then, with the front part of my head a slight yellow-y blonde, and the rest left a dark, deep, virgin Asian black. And it’s pretty cheesy to say that blondes have more fun, especially when I was at most 30% blonde, but I immediately did feel better about how I looked, and my bob was a little less “fuck-ass” when I’d look at myself in the mirror, just because of those two streaks covering my eyes. All of a sudden it went from accidental Edna Mode to something meticulously planned.

When I was scrolling through TikTok one day, I came across a video of Jess Tran, an Asian woman who had dyed her hair back to black after seven years of being blonde. She cited a large part of her experience as an Asian woman as feeling invisible, and feeling like you had to drastically change your appearance to make yourself hypervisible. “[I was] stepping away from this like, traditional idea of femininity and beauty that I felt shackled to.” Her fear of dying her hair back to black resonated with me so deeply, that in some way I would become more “boring” by sporting my natural hair color. It’s a little heartbreaking to think about: that I felt the dark, sleek black hair I was born with felt unremarkable to me. But Tran dyed and cut her hair as an external representation of her internal experiences, but also due to a need to feel “special”, which is something that I personally felt I couldn’t articulate.

Growing up in New York my whole life, I’ve never experienced feeling isolated because I was Asian. It was amazing to grow up around other children who celebrated Lunar New Year and spoke multiple languages. I moved through the world not having to consider my place as Asian, American. Everyone around me felt the same to me, like we had this mutual understanding we would grow up to live on the cusp of completely integrating to popular American culture or take a step in the other direction and embrace the country our parents left. It was not a dichotomy that revealed itself to me in the past, but as I navigated the world and met people who seemed to be so sure in their identities, it was one that became overwhelmingly clearer.

I knew I didn’t want to emulate whiteness by changing my appearance;I wasn’t trying to seem whiter or any less Asian by dying my hair. But I do think there was a separation I was trying to make between my Asian self and my Asian American self, that in an attempt to seem less invisible, I had to turn my appearance from Asian woman to Asian American woman. Because to me that meant a certain strength and independence and confidence in moving about the world. That maybe the further I removed myself away from my Chinese identity, my American identity, which was full of ideals about independence, self-realization, and self-expression would become representative of who I was as a person.

I think I found my own invisibility when I started meeting Chinese people who had come to the States for high school or college. In my head they were so put together, such perfect representations of Chinese girls.. They spoke flawless Mandarin, much different than my “everywhere accent” gained from growing up in a Cantonese household in America, and seemed to have so much self confidence. They seemed to lack an insecurity that I felt about my own appearance, they knew exactly what that wanted to look like and what they wanted to present themselves as. And when they spoke amongst themselves I felt left out, a little in part because of me not understanding the Mandarin slang they’d use, it seemed like they .

It felt like I was inherently different, which I guess I was.

I guess I ask myself, am I visibly American? Can they tell I was born here? And somehow there’s an insecurity, especially around Asians from Asia, of being diaspora. It’s an age old tale of Asian Americans not feeling entirely like they belong in either place, and my need to become hypervisible was felt because I thought I, as an Asian American, was less visible to both the non-Asian public and the Asian one. I began to chase this “visibly American” to liken myself to the Americans around me, and bleaching my hair blonde was my way of becoming seen by those around me I felt invisible to. And it worked, I got compliments on my hair, from random baristas to old friends I had known for a while. I still remember when I walked into school on the day I changed my hair, I met with a chorus of people telling me how “well it suited me”. I was affirmed in my decision, knowing that before dying my hair, I would get mistaken for other Asian girls with pin-straight Asian bobs and now, people I had never even formally met remembered me.

I’m not sure if I want to reinforce my American-ness or my Asian-ness by deviating from the “good Chinese girl” look my parents probably were used to. No one looks at someone with a split-dye and thinks “that’s the look that traditionally every Chinese parent wants for their children”. But it became a physical manifestation of this excuse I’d tell myself and others when I was only able to read two characters in a Chinese phrase or held my chopsticks wrong: “I’m American. I’m not your ordinary Chinese girl because I grew up with Kraft, speaking to my dad in English, and believing in individual happiness over filial piety.” As an American, I feel that my unique experience growing up as a racial minority in this country makes me hyper-aware of the failings of the “tame Asian woman” stereotype, but as I try to differentiate myself from that caricature, I struggle with the way I represent that, especially to myself.

I sought an understanding about my own identity, which in part revealed itself to me in a reading by Jacques Lacan, The Mirror Stage, where he theorizes that past the beginning of toddler hood, we begin to recognize the image we see in the mirror as ourselves. But there’s a moment of frustration when we realize the person we see looking back at us is ourselves, when our motor skills, our physical ability hasn’t developed enough to move as autonomously as the baby staring back at us. This pseudo-toddler, who we recognize as ourselves, is put together and whole, but also not whole as there’s no substance, it’s a reflection, an avatar that we only project our entire being onto. And so begins the paradox where we try to become who we see in the mirror, when the person we see is none other than ourselves in the first place.

And it’s a little comforting to think about how this disconnect with your own reflection is something philosophically thought about because I’d feel really bad about being taken aback by my own Asian face. I felt a sense of guilt about wanting to change how I looked to feel special, to feel seen.

But how could I really seek to define who I am as a person through my outward appearance? While I may change how I present myself as a reflection of parts of my inner self, the avatar, the person I see reflected back to me in the mirror cannot encompass who I am. It kind of goes both ways, I know what I see in the mirror will never as a whole represent who I am, but also she is an unreachable idealization of myself I want to show other people. She is a tool I use to feel a little less invisible internally, but true visibility is a form of self acceptance. I’ve come to some sort of understanding, that my outer self is not a signifier of not only the person I am on the inside, but any of these identities I choose to take on. I can’t change the fact that I am a Chinese woman, and will carry that face with me my entire life, as will I carry my American identity.

After going through all this in writing, it seems a little clearer to me what I was and still am looking for: both belonging and individuality. It was something that I wanted to achieve by altering my physical appearance, but in that process, I was overlooking the concepts I had internalized as a woman in American society, that both made me insecure about my Chinese-ness and unwilling to champion it. In truth, I think less so than an internal battle between my Chinese and American identities, I was in search of a label that fully encompassed myself and my experiences as a whole. And it’s a duality that I will probably have to try to balance for however long I’m alive.

I still have more crazy hair colors to try before I go back to my natural color, but I hope that when I do, rather than alienating, it feels like finally finding comfort in the entirety of the person who looks back at me in the mirror.

Cynthia Li is a second year majoring in Studio Art. She has a passion for creating, and hopes through writing and artmaking, she can contribute to Generasian’s ongoing mission of sharing Asian voices.

0 comments on “Refractions”